Unless you’re a very recent follower of ours, you’ve heard us talk surpassing well-nigh “contributory negligence.” To recap: “pure contributory negligence” is the law in North Carolina and only 3 other states (Alabama, Virginia, Maryland). In pure contributory negligence states, if a person is injured by someone else’s fault and the injured person contributes plane the tiniest percent (1% is enough) to their own injuries, they collect no damages. In “comparative fault” states, the injured person’s damaged are reduced by the value of their fault.

North Carolina’s contributory negligence law applies to everyone, but as you can imagine, it has an expressly unfair impact on injured bicyclists. People yank unrepealable conclusions, based on their life experiences, when you tell them well-nigh road collisions. For example, if you’re in your car and hit from behind, everyone assumes the suburbanite coming from overdue is at fault. If you then add that the person who was hit from overdue was on a bicycle, the outlook shifts; they seem that the bicyclist had at least some fault – they weren’t where they were supposed to be, they should have gotten out of the way, etc. It takes a lot of work and wits to dispel these notions and, in North Carolina, the failure to do so properly usually ends immensely for the bicyclist.

Contributory negligence reared its ugly head, as it unchangingly does, in a bicycle specimen we tried last week to a jury in Cumberland County. We write-up it.

First, the history of the case

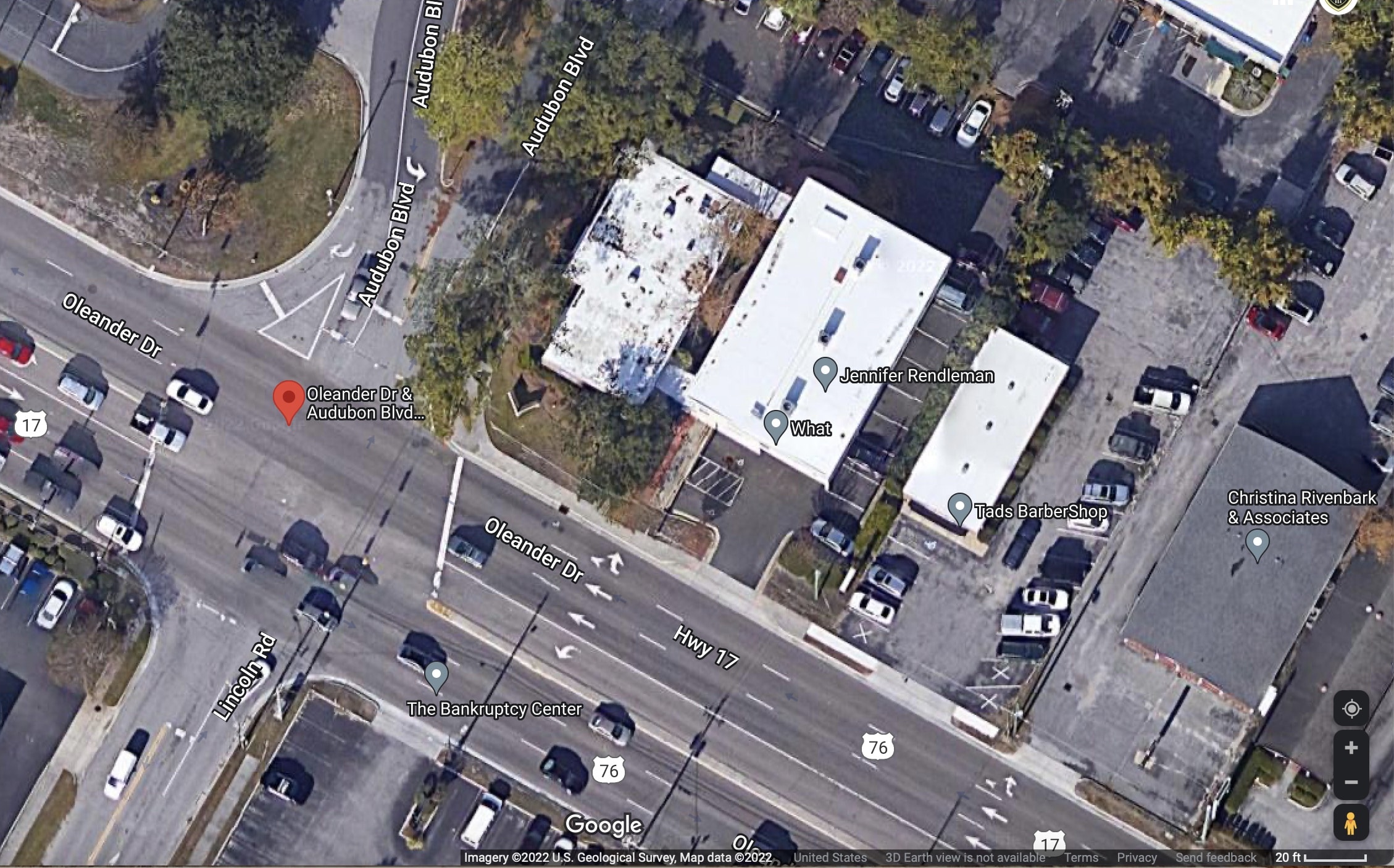

The crash took place in Wilmington, North Carolina, on Oleander driver. The suburbanite was driving West on Oleander and ran a red light. Our client, on her way to her graduate school classes, was planning to navigate Oleander on her bicycle. She arrived at a red light at Lincoln, the crossroad of Oleander, stopped, put her foot down, and waited. Her light turned green, and she rode forward. She made it past at least 3 lanes of East unseat traffic surpassing the suburbanite ran through the red light at 45 mph and slammed into her.

Unfortunately, the bicyclist suffered a concussion and memory loss. The last thing she remembered was her light turning green, looking to make sure it was safe, and going forward. Her next memory, a unenduring one, was from the ambulance ride and then nothing until later while she was in the hospital. The suburbanite and her passenger told the officer at the scene that their light was yellow. Based on that information ONLY, the officer wrote our vendee a ticket!

It gets worse: a young woman was walking from a parking lot to her job when she saw the crash. She saw the bicyclist crossing on the untried light, saw stopped cars at the intersection and saw the suburbanite wrack-up past the stopped cars and plow into the bicyclist. As the suburbanite unfurled driving through the intersection, the young woman ran to help the bicyclist and tabbed 911. The young woman tried to requite the officer her information and he never wrote it down. The only reason we knew she existed was that, very shortly without the crash happened, the bicyclist’s parents visited the various businesses in the intersection. They knew that people had come to their daughter’s aid and wanted to thank them. The receptionist at one of the businesses, told them that their intern, the young woman, had seen the crash.

Another woman’s name had made it onto the officer’s report, but he misstated what she told him. The officer said that the witness told him that the suburbanite had the right of way. When we talked with the witness, and her passenger, she insisted she had told him the other way around: that the bicyclist had the right of way. She signed an testimony to that effect and traveled to Fayetteville to testify at trial.

The first step was to make sure that our vendee was worldly-wise to get the traffic ticket dismissed. With her stellar driving record and affidavits from the two women, and the one passenger, the New Hanover County District Attorney’s office threw out the case.

We then turned our sustentation to the starchy specimen to struggle to resolve it. Long story short, there were some negotiations, but the defendant suburbanite never took responsibility for running the red light. Over time, she told several variegated stories well-nigh where she was when, she claimed, the light turned yellow. She did not know what lane she was in or whether there were other cars in front of her or abreast her. She did not see the bicycle rider until the moment of impact so could not say anything well-nigh what the bicyclist was doing.

On November 14, we started the jury trial.

The two women both came to Fayetteville to testify. The young woman testified first and was resulting with her older statements that our client’s light was green, that other cars on Oleander were stopped, and that the suburbanite hit the bicyclist. Her testimony wasn’t without a hitch though, as she somehow remembered our vendee stuff in a crosswalk (there wasn’t one). We showed her some photos, including one she had taken, which refreshed her recollection.

The other woman really struggled to understand the questions and what was stuff asked of her. She testified that our vendee had the right of way and the untried light, and that the suburbanite “was trying to write-up the yellow.” She didn’t realize, apparently, that the bicyclist’s light couldn’t possibly be untried while the driver’s was yellow. The only subtitle we can think of is that she heard the trial opening statements and drew some new conclusions in her head. Thankfully we had the statement she wrote for us just a few months without the crash.

Our vendee was the only other person we had misogynist to testify well-nigh what happened, and she didn’t have much to add, considering of her concussion. She testified that she traveled that route daily to school and had never run a red light and never had any trouble crossing the intersection. Surpassing overly riding to school, she had visited a local velocipede shop to ask well-nigh the weightier route to take and bought lights and other safety gear for her bike. We hoped that there was no way anyone would believe this very meticulous person would jump a red light to navigate 6 lanes of rush hour traffic.

The defense presented the suburbanite and her passenger as witnesses. The passenger unmistakably never saw any kind of light surpassing the standoff and was repeating what her friend told her. The suburbanite told her third story well-nigh when the light turned yellow. (The first two were in her deposition). The defense moreover tabbed a traffic engineer to talk well-nigh the timing of the lights. We thought he was helpful to us, in that he established (1) there was no way the driver’s light could be yellow if ours was untried (seems obvious, but you never know!), (2) if the young woman witness was seeing a untried light, then the opposing light, for the bicyclist, was moreover green, and (3) it was possible for someone on a bicycle to trip the light.

The tuition priming and verdict

The tuition priming is arguably the most wearisome part of the trial. It’s where the lawyers and judge confer well-nigh the law that is to be given to the jury to use to decide the case.

The tuition priming is moreover a part of the trial where it hair-trigger to have an experienced “bicycle attorney.” Not understanding the operation of bicycles and the interaction of bicycle operation and the law can be fatal. I have tried cases where the defense has no idea how a bicycle operates nor fully understands the law as it pertains to bicyclists, and I have been worldly-wise to educate the judge on both of those things.

As we often do, we asked the judge in this specimen to NOT instruct on contributory negligence. The judge felt that, based on the law, he had no choice, and we lost that battle. That meant, for us, a very long latter argument, explaining what contributory negligence really ways and what it does not mean. I told the jury that riding a bicycle is not contributorily negligent, no matter how they themselves, finger well-nigh riding a bicycle on the road. I told them that not stuff worldly-wise to anticipate, when you leave a untried light, that someone who is at that point probably a hundred yards yonder is going to tideway and wrack-up through the red light, is not contributory negligence. And I told them that not wearing a disco wittiness on your throne (or reflective suit in the middle of the day, as the defense often argues) to zestful people who aren’t looking to your existence, is moreover not contributorily negligent.

We moreover had to dispel defense arguments that we knew were coming, based on the property damage. As a result of the crash, the driver’s side mirror had been wrenched off, there was a wafer in her door, and a wafer to the rear of the car. The defense argued that this meant that the bicyclist had run into the side of the car. That seems logically impossible, with the bicyclist likely going 10 mph and the suburbanite at 45 mph, but it’s nonflexible to oppose without an expert engineer and the specimen didn’t warrant us hiring one. We knew, however, that you can’t taco a rear bicycle wheel by ramming headfirst, perpendicularly, into the side of a rock-hard obstacle. I told jurors that it was much increasingly likely that the suburbanite hit the front of the velocipede (also limp the front wheel), and that the car’s momentum, spun the velocipede virtually and dragged the bicyclist withal the side, smashing the mirror and denting the side in several places. My treatise well-nigh this, pre-trial, felt like vibration my throne versus the wall. Thankfully, the jury got it.

The verdict

It took the jury 2 hours to come when with a verdict. They had one question for us during their deliberations, which was to ask for all photographic vestige that had been introduced. We sat, holding our breaths, as the clerk read the verdict. (This process takes well-nigh 10 minutes and seems like 2 hours).

On the first question: Did the defendant, by her negligence, injure the plaintiff? Answer: YES

On the second question: Did the plaintiff, by her own negligence, contribute to her injuries? Answer: NO

To think that when we took this case, our vendee had a ticket for running a red light. It was a 3-year wrestle that ended with a win versus contributory negligence. The jury decided that the defendant should, finally, take responsibility for her negligence. But with way increasingly effort and disruption to our client’s life than necessary.

Once again, it is time to put this ridiculous law to bed and enact the much fairer law of comparative fault. We don’t mind taking responsibility for our own actions, but insurance companies have used the extremeness of this law to their wholesomeness to the point where it is difficult, if not sometimes impossible, for injured people to seek justice.